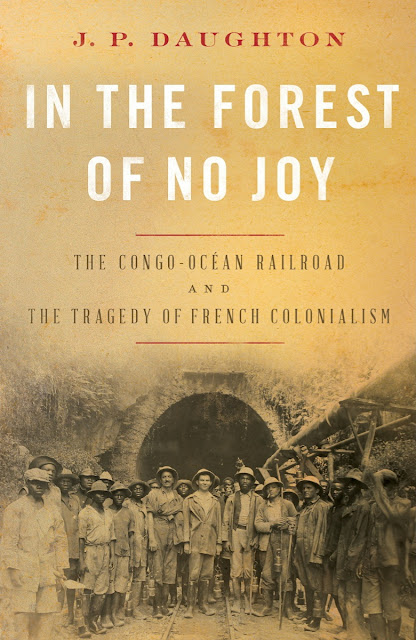

"From 1921 to 1934, men from “the Batignolles” lived near the coast in Middle Congo, often referred to by the French as simply “the Congo,” a region in the southern part of French EquatorialFrom 1921 to 1934, men from “the Batignolles” lived near the coast in Middle Congo, often referred to by the French as simply “the Congo,” a region in the southern part of French Equatorial Africa. They worked on building the Congo-Océan railroad, a massive construction project that the colonial government undertook in the years just after the First World War. Long heralded by Frenchmen as essential to the economic development of the region, the railroad would connect the city of Brazzaville, the colony’s largest settlement

on the upper Congo River, to Pointe-Noire, on the Atlantic coast, where the French planned to build a deepwater port. Covering only some 512 kilometers, fewer than 320 miles, the railroad was not terribly long. But it crossed difficult terrain, especially the dreaded Mayombe, where the rails wound atop unstable, sandy soil, through a region of thick forests, mountains, and gorges." From In The Forest of No Joy

Prior to today's work I have read two very good accounts of the exploitation of the people of the Congo area of Africa by Western countries in order to enrich themselves on the incredible natural resources of the Congo.

Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives By Siddharth Kara details the extreme cruelty with which modern Congo residents are treated while mining cobalt. Cobalt is essential in batteries for vehicles, tablets and smart phones. Workers are paid around $2.00 a day.

And

In King Leopold's Ghost by Adam Hochschild I learned of the millions of residents of the Congo who died collecting rubber for tires.

To me there is a deep sadness in the exploitation of incredibly impoverished Congolese used to produce essential supplies for cars, knowing the having of such a vehicle would be an impossible dream for them.

An unwavering belief in white supremacy was an article of faith to Europeans working on the construction of the railway.

The story of the Congo-Océan certainly

demonstrates all too clearly the devastating potency of assumptions of racial superiority. But the faith that France could accomplish the impossible, that it could transform the Cinderella of the empire, was also an essential theme in the tragedy. The chief administration of the project were educated French men, many of the front line supervisors were from other parts of Europe. The French brought in African soldiers from other regions to supervise railroad workers. Whopping and worse was commonly employed. The Congo workers were seen as lazy, stupid, and without a work ethic.

The narratives of empire that were spun in defense of the railroad were worrisomely effective at burying prolonged human misery, the deaths of thousands of people, and the disappearance ofcommunities. They even helped Europeans claim credit for building a railroad across an unforgiving forest while simultaneously erasing the sacrifices of the tens thousands of men and women who made it possible. For the French who oversaw the Congo-Océan, white triumph would always discount African trauma. The narratives and ideals thatanimated liberal empires have not been entirely dismantled in the wake of decolonization. The voices and experiences of the men and women who worked on projects offer one line of defense against future hubris. In their stories is the wisdom needed to see the potential duplicity of those who confidently inspire with promises of transformation, wealth, and humanity.

The were reports made to French authorities about the atrocities. Andre Gide spend time there. He was shown totally perfect conditions in camps, well fed healthy workers.

In a kind of cosmic revenge many medical scholars think Aids orginated in the area of the project about 1930, eventually killing millions.

In the Forest of Joy is very illuminating. (It is a trifle repetious.)

J. P. Daughton is an award-winning historian of modern Europe and European colonialism and has taught at the University of California, Berkeley, and Stanford University. He has provided media commentary for the Atlantic, Newsweek, Time, and CNN. He lives in San Francisco, California. From the publisher

Mel Ulm

No comments:

Post a Comment