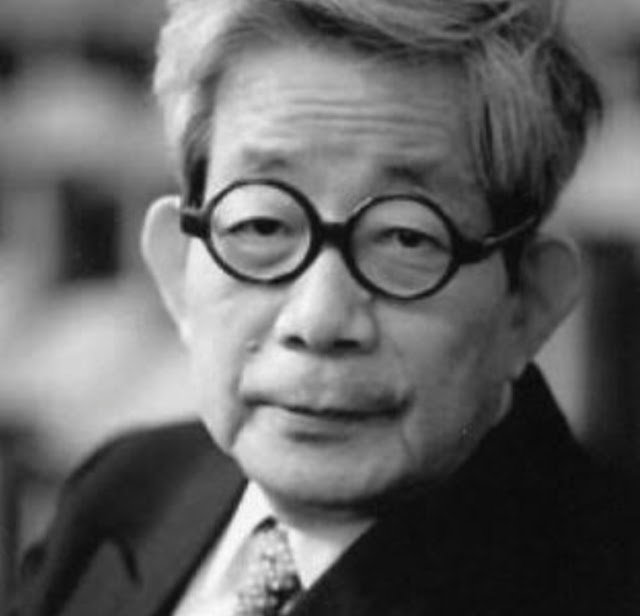

Kenzaburő Őe - January 31,1935 to March 3, 2023

Kenzaburo Oe has departed from us. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1994

I first began reading his work in April of 2009. I have posted upon 19 of his works.

His life and body of work is celebrated throughout the world.

"The image of Daio in the forest reminded me of the twokanji—淼淼 and森森—that suggest infinite expanses of water and forest, respectively, and thinking about those pictographs made the dream feel even more luminous and prophetic. In my dreamy vision, the relentless torrents of rain had saturated the leaves of the trees with such a vast amount of water that the entire forest seemed as deep and as wet as an ocean."!From Death by Water

I first encountered the work of Kenzaburo Oe in 2009 during JL2. I knew right away I wanted to read everything by him I could. Here were my thoughts from long ago on his stunningly powerful story “The Day He Himself Shall Wipe Away My Tears”:

“I cannot really begin to convey the strange and wonderful qualities of this work. Imagine if Rabelais (Oe was a student of French literature and philosophy at the University of Tokyo), Jean Paul Sarte and William Burroughs collaborated on a work right after eating some very bad blow fish and you have an idea of how

The Day He Himself Shall Wipe Away My Tears feels like as you read it.

This work is about a lot of things and it is about itself. It is about loss of faith, feelings of profound loss,

survivor's guilt, and the destruction of old values. We feel the effects of the war everywhere.

The Japanese culture provided no role models or cultural archetypes to help them cope with what could not happen, total defeat.

There is a long established literary tradition of using the insane to say what cannot be accepted by those in fully sunlit worlds. The narrator of The Day He Himself Shall Wipe Away My Tears has very deep roots in western culture. His ancestors were in the plays of Euripides, his great grandfather was Dostoevsky's underground man, he speaks through Crazy Jane. Oe has stated that he has come to understand the meaning of his own works through reading the poetry of William Butler Yeats.

I do not mean to convey that The Day He Himself Shall Wipe Away My Tears is a closed work that cannot be enjoyed or even followed without great effort. It can be enjoyed just as a narrative of a crazy person. As such we will pick up a lot about the aftereffects of the war on Japan. We will see how the Japanese people felt when they heard the Emperor speak on the radio, and we will learn something about the home front in rural Japan. The book is also funny-imagine the very straight laced executor of the narrator's estate being threatened with the loss of his work as administrator of the narrator's estate (who appears to have nothing to pass along anyway and probably is not going to die soon either) by a man in an underwater mask. Oe is as deep as the Russians and as careful as Proust and Flaubert and knows as much about people as Dickens.”

"Simple. They were basically scared. They can't approach a man as terrifying as Big Papa without costumes, without painted faces...Able official turned to Dog Face and they both burst out laughing...But once they get going so that the merriment

can start percolating, they'll crack the audience up, so they will join in the laughter themselves...";From The Pinch Runner Memorandum

My thoughts on An Echo of Heaven

An Echo of Heaven is one of the most overtly "philosophical" of Oe's works. It is the story of a woman whose two handicapped sons committed suicide. It focuses on her attempt to make sense of and cope with the impact of this event on her life. It is not what I can call an "open or easy read" compared to some of his other books. If you are into Oe you will for sure love this book.

An Echo of Heaven is a strange book. It is partially told in long letters from the woman whose sons killed themselves, Marie Kuraki, to the narrator of the story who has agreed to write a book about her to be released in conjunction with a movie a friend of the narrator is making about her. Much of the novel is set among Japanese living in rural Mexico, some went to escape living in post WWII Japan. Marie lives there and has become a saint like figure to the Mexican agricultural workers. She has also joined a religious cult whose leader is called "big daddy" and she is described as looking like "Betty Boop", an American cartoon character. She writes very long letters(10 + pages) about her involvement with the religious cult. I think this is part of Oe's account of the nature and origin of religion. Marie seems at times to throw to her self into a lot of sexual activity, a lot of drinking and meaningless activities in an effort to cope with the death of her sons. One of them was in a wheel chair, both were mentally handicapped (as is one of Oe's children). They agreed to kill themselves. One boy pushed his brother out into the ocean in his wheel chair and then drowned himself. The reasons for this are not made super clear and there is no indication Marie is at fault.

The more I think about it, the more I feel this is among the very deepest most amazing of Oe's work. It is near R rated in parts (I would have to say the sex scenes in Oe are often more about power than pleasure, more about using sex to drive thought out of your mind.). There is a big symbolic import to having the novel set among Japanese living in Mexico (and the USA) and the narrator and Marie both characterize Mexican men as aggressive macho types and the women as used to a harsh life. Marie went to Mexico to help rural Mexicans. Oe also taps into the religious beliefs of the pre-Colombian residents of Mexico and the effect of Catholicism on the lives of the Mexicans.

The narrator of this story is very into the work of Flannery O'Connor and I was very glad I have recently begun to read her work. In one really enjoyable scene the narrator goes into a Mexico City bookstore and buys up all of their works by O'Connor. He asks the clerk if they sell a lot of her work. She says no not really but every once and a while someone will come in and buy all her work. (Probably there have been dissertations written on the Oe/O'Connor connection.)

The narrator is also into Yeats, Blake, Balzac and a few other western Canon status writers but it is O'Connor that is most important here. I think one reason I am drawn to Oe is that he does talk deeply about authors I love in his work. To me it speaks to the depth of Oe that it is not simply that he shines a light on Yeats, Blake and O'Connor but they do so on him as well.

Some readers of Oe who want to shy away from seeing him as an atheist try to see him as thinking along the same lines as the Romanian philosopher Marcea Eliade. I think this is a false almost wishful thinking reading of Oe and represents a shallow understanding of his work. I always think back to his Hiroshima interview with an elderly woman whose whole family were killed in the atomic bomb attack and who was suffering from radiation burns.

Iv see him as creating wisdom much as I see Samuel Johnson as doing. The wisdom of Oe is that of a world turned inside out on itself, that of Johnson is of a world sure of itself. The best of Oe feels not so much written as discovered.

A Personal Matter is the most popular of the novels of Oe. The central character Bird is very hard to like, in part because it is hard not to see yourself in him. His estranged wife has given birth to a son who seems to have a severe birth defect resulting in terrible brain damage. Bird secretly wants his son to die but he must go along with the doctors who say they can possibly operate on him once he gets stronger and save him. Bird is not gratified by this as the odds are very high that the child will be severely handicapped mentally. Much of the few days in the life of Bird we see him trying to escape from thoughts pressing in on him that he knows are a violation of acceptable morality. He wants very much to go on a trip to Africa and he spends a lot of time thinking about this. He indulges in a great deal of sexual activity with an ex-girl friend that he care little about, he drinks too much, he gets fired from a job he does not like, and shows little real interest in anything. He does love the poetry of William Blake.

A Personal Matter is saturated with animal references and metaphors. I did an informal count as I was reading the novel and there are about 150 such references.

The meagerness of her fingers recalled chameleon legs..the toad like rubber man rolling the tire down the road....Bird stared for an instant in the numerous ant holes in the ebonite receiver...the glass chatter at the bottle like an angry rat...like a titmouse pecking at millet seeds..like an orangutan sampling a flavor..Bird and Himiko exchanged magnanimous smiles and drank their whiskey purposefully, like beetles sucking sap..whiskey-heated eyes dart a weasel glance...

There are numerous references to sea urchins, grasshoppers and shrimp. Some of the animal references are amazing in their cleverness and all of them made me see more deeply into the world projected by Oe. (Oe has a brain damaged son.)

A Personal Matter is a very intense work. Once you realize the central character Bird wants his son to die it is hard to like him and also hard to admit we do not understand why he feels that way. The novel is very explicit sexually. Attitudes toward suicide are considered briefly. A Personal Matter kept me in suspense throughout. I wanted to learn what would happen to the child and how things would turn out among Bird, his wife, and his girlfriend. Oe is not afraid to look a monster in the face. His work can help us do the same and if it turns out one of those monsters is buried within ourselves and our mythic past then at least we know it. (in Hiroshima Notes-a work of nonfiction) that he never admired the courage of anyone more than when he saw she was facing this horror without religion."

Hiroshima Notes by Kenzaburo Oe (trans. from Japanese by David Swain and Toshi Yenezawa, 1965 and translation 1981, 192 pages) is a collection of essays Oe published after making several visits to Hiroshima in 1965 to attend observations for the 20th anniversary of the dropping of the Atomic Bomb August 6, 1945. It also includes a useful introduction by David Swain and two prefaces by Oe.

Hiroshima Notes is a deeply wise book by a man who has thought long and hard on topics most would prefer to move on from. It is far from a bitter work. I want to relay few of the things in the book that stood out for me.

The survivors of the atomic bomb blasts were the very first of the Japanese people to say that the bomb blasts were the fault of the Japanese military government. Oe feels that the dropping of the bomb was a war crime also. My first reaction to this was to say that it saved, among other, the lives of millions of Japanese. (I recall a few years ago I watched a movie from 1944-it was just a very minor movie and I do not recall the name. Some English school children were looking at a future globe of the world. They asked the teacher what the big empty space in the Pacific Ocean was. The teacher laughed and said that was where Japan used to be.) Oe, agree or not, is suggesting in doing this a force was turned lose on the world that could one day bring an end to human life. Never before could war do this. It might have been that the Japanese would have surrendered facing a joint American and Russian Invasion (the Japanese knew the Russians would without hesitation send millions of their troops to be killed and that they wanted very much revenge for their defeat in the Russian Japanese Naval War). Both the Japanese and the Germans were working on Nuclear weapons and clearly would have carpet bombed Australia and England with them and the USA if they could reach it with the planes of the day. It is also true that the Japanese would have been defeated by nonnuclear warfare. (I personally feel Truman did what he had to do) In Hiroshima in 1965 there were 1000s of women who were children when the bomb went exploded. They survived but were so badly scarred that they began essentially life long hermits ashamed to go out in public. No one would marry them as they were thought to be unable to give birth to a healthy child. There were also in 1965 thousands of older women living alone who were the only survivors of their families. Some of the young girls who survived did pray daily that no one else ever experience what they did. Some wanted all the world to go up in a nuclear war. The Japanese government, aided by American occupation forces, did provide medical care to survivors but they did not provide living expenses so many of the injured had to keep working to support their families so could not take treatment.

The doctors who lived in Hiroshima when the bomb exploded soon became the first authorities on the medical effects of the bomb. They also suffered the effects. Rates of leukemia went way up as did other forms of cancer. Suicides went way up throughout the lives of the survivors. Oe tells us a very moving story. A twenty six year old man, age six when the bomb exploded, is advised he has two years to live as a result of leukemia. He can live out his remaining time in a charity hospital ward. He chooses to work at hard labor (he has no skills) so he can live on his own and be with his 19 year old fiance, not yet born when bomb exploded. When he died she took an overdose of sleeping pills stating that her death was also a result of the bomb blast. There are other equally moving stories. We see the wisdom and power of the doctors. We feel a little ashamed when we see different groups fight over who should run the 20 year anniversary memorial but we are also moved by seeing good people from all over the world come together.

Oe says the greatest gift of the bombing is the wisdom of the survivors. Oe is clearly humbled by his task of bringing their stories to life.

The youngest survivors of the bomb are now in their middle sixties. There are ninety year old survivors that still bear the scars.

I know I do not have the ability to convey the power of this book. I know most people do not want to dwell on these matters. I am pretty sure my daughters and children throughout the world can graduate from college and never be told of them by a teacher. As I read the book, I hope this remark bothers no one, I thought that Oe was the kind of man who could have written the wisdom books of the Old Testament. At one point he has a long conversation with an elderly woman. He says her wisdom is so strong that she is able to live a life scarred since her middle years by the blast without a belief in any authoritarian creed. Oe does not say that wars are started by those who follow authoritative codes, much of his wisdom is in what he knows he cannot say.

Hiroshima Notes deeply effected me. I felt an almost Oceanic Feeling come over me as I thought about the book and what I could attempt to say about it.

To those new to Kenzaburo Őe I would suggest you read through his works in publication order.

Mel Ulm

.jpg)